Development Log: Melody Asaresh Moghadam

Just a few weeks after I started working with the Reckonings Project as a research assistant, I got to be a part of the team representing Reckonings at the Jazz Square Celebration that happened on September 27 and 28, 2024. Those two days of celebration were dedicated to the legacy and influence of jazz on the city of Boston, its neighborhoods, and communities. Jazz enthusiasts gathered to celebrate the clubs that are or had been located around Jazz Square, at the intersection between Massachusetts Avenue and Columbus Avenue in Boston, as well as the musicians who played in these clubs. Due to my background in music performance, I was thrilled to be involved and contribute to the project. In addition to listening to some outstanding music that was performed at The Red Room at Café 939, at Jazz Square, and in front of Coretta Scott King’s apartment in a brownstone, Jazz Square came with so many new experiences and exciting surprises for me.

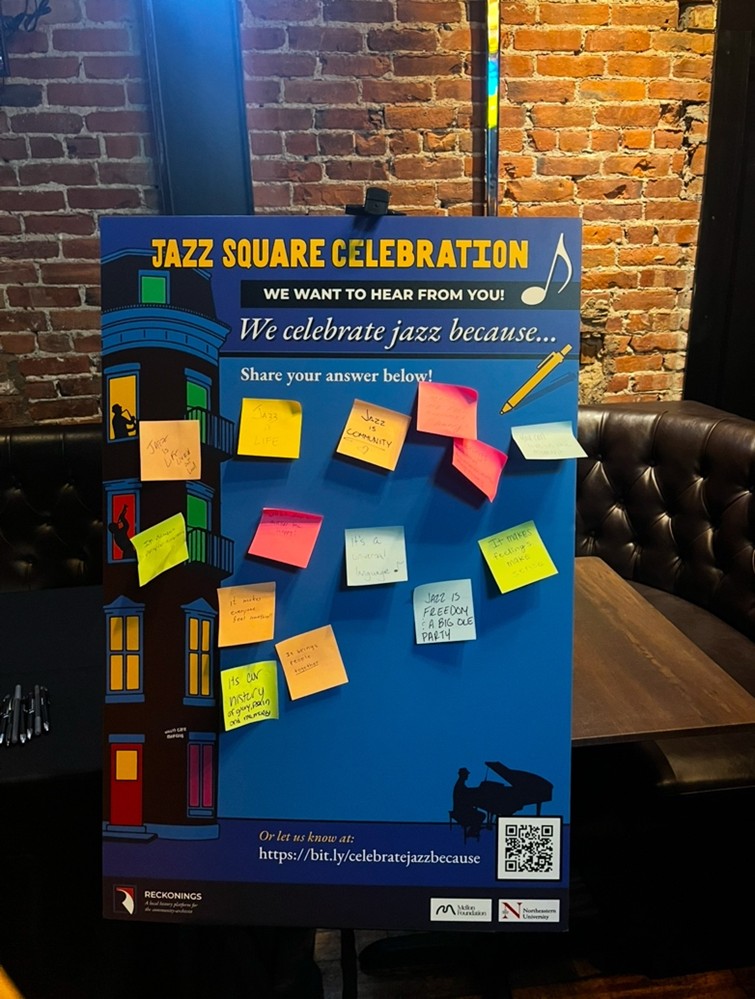

At the Jazz Square Celebration, the Reckonings team provided opportunities for community members to express their opinions and explore their relationship with jazz by responding to two prompts: “Jazz Square matters because…” and “We celebrate jazz because…” In the lobby of the Red Room at Café 939, at the Reckonings table, while I was chatting with people and encouraging them to respond to the two prompts by writing on a sticky note, something very exciting happened. I met Karen Cowan who responded to the prompts by mentioning her father–Sabby Lewis! At that moment, I still did not know who Sabby Lewis was, but we had a lovely conversation. Soon, I found out that I had been missing out on knowing one of the greatest Boston musicians, who contributed so much to Boston’s Jazz scene, and who played at Jazz Square venues between the 1930s to 1960s. Karen told me about how she had been preserving handwritten music scores, pictures, and artifacts belonging to her father. In the right hands, Karen wished to donate them to a trustworthy institution so they can be used for educational purposes. I enthusiastically told her that Reckonings is a local history project for community-archivists, and we would love to help her find wherever is best suited for her archives. We exchanged numbers, and Reckonings has been in touch with her ever since. We have been trying to find the best location for her archives so it can be well preserved and used by other jazz enthusiasts as a be part of Sabby Lewis’s great legacy. This experience was very fulfilling for me. I got to utilize and connect the musician side of me to the project that I was involved with as a historian and a researcher. Moreover, it showed me how extraordinary and rewarding it is for a historian to be directly engaged with her community!

After the Jazz Square Celebration, my attention shifted to my main assignment at Reckonings, researching the history of African American Master Artist in Residence Program (AAMARP). AAMARP was established in 1977 by renowned and distinguished artist and activist Dana Chandler at Northeastern University. This was the first artist-in-residence program for Black artists in the United States. AAMARP and its studio space soon became an influential part of the Boston art scene, providing numerous opportunities for artists with different backgrounds. Dana Chandler wrote in a letter to the Boston Phoenix in 1980, “while AAMARP is a residency program for Black Artists, and very proudly has an African-American cultural base, it is programmatically multi-cultural and multi-ethnic. In other words, AAMARP is for everyone.” When digging through Northeastern’s AAMARP’s archive, I found exciting exhibitions involving Arab Artists, Asian Artists, and Hispanic Artists. AAMARP was also very involved in its community, actively mentoring young artists, and had many collaborations with Boston Public School. The program provided a platform to feature music, poetry, and film. There is no doubt that AAMARP was truly for everyone.

My research on AAMARP became very multi-dimensional as it involved art, activism, multiculturalism, the history of Boston and so much more. I had the opportunity to choose what I wanted to focus on and how I wanted to expand my research, with an end goal of creating a small archival collection/exhibit of documents/artifacts to put on Omeka S (basically creating a small website) to be used at Northeastern University and by others for educational purposes. It was difficult to choose a topic, as there were so many interesting routes that I could go. However, since I only had a few months with the project, I decided on two collections.

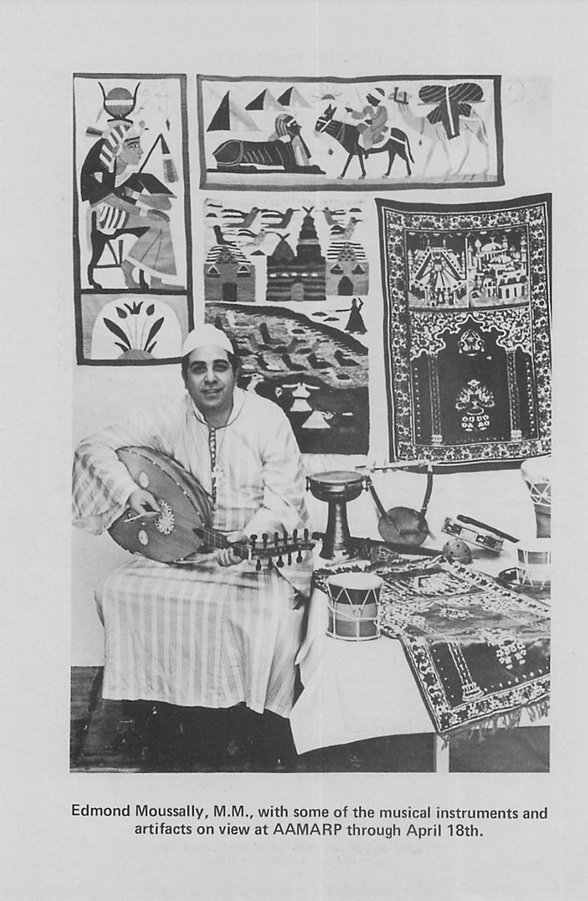

The first one is on the Contemporary Arab World Exhibition that was held in 1979. The exhibition became very interesting to me as it was such a wonderful example of multiculturalism at AAMARP. It featured photos, books, maps, and folk dances and music from Egypt, Syria, and Lebanon, gathered and performed by ethnomusicologist Edmond Moussally. I was also interested in Dr. Moussally himself. He was raised in Boston, got his first music training at South End Music Center, and obtained his higher education degrees at Boston Conservatory of Music and Boston University. He stayed and contributed to Boston’s art and music and taught at Roxbury Community College. I really wanted to get a chance to interview him, ask him about his experience with AAMARP, and the Contemporary Arab Exhibition that looked so fascinating to me. However, I was not successful in reaching him.

The second collection I gathered was based on a manifesto that Dana Chandler delivered in 1970, demanding that the MFA (Museum of Fine Arts Boston) eradicate institutional racism. In the 1960s and 1970s, Chandler was active in the Black Power movement, and his artworks reflected the traumas and brutalities that African Americans were going through while showcasing their demand for equality, creativity, and culture. In the same year that he delivered the manifesto, he created “Fred Hampton’s Door.” The piece was a reaction to the assassination of Fred Hampton, the leader and chairman of the Chicago chapter of the Black Panthers, by the Chicago Police on December 4, 1969. Dana Chandler’s manifesto pressured MFA to hold “Afro-American Artists: New York and Boston” exhibition from May to June 1970. The exhibition was a collaboration between Museum of the National Center of Afro-American Artists, the Museum of Fine Arts, and the School of the Museum of Fine Arts. Curated by Barry Gaither, this was the largest group exhibition of contemporary Black art at the time. The exhibition received recognition across the country, showcasing art works of 70 artists, including Calvin Burnett, Jerry Pinkney, Betty Blayton, and many others.

This was my first semester as a PhD student in World History, and Reckonings was a great kick start to my journey. Reckonings took me to so many interesting places, introduced me to so many wonderful people, and showed me so many impressive artworks and music both in the real world and through my research. Even though I am moving on to my next assignment for the following semester, I am so excited to stay tuned to Reckonings’ next projects, the progress of research on AAMARP, and to hear where the Sabby Lewis’s Archive will end up.